Upon receipt of the Infringement Notice, you have only a short time frame to signal your intention to dispute the fine. Page 2 of the Infringement Notice sets out your options – either pay up, dob someone else in, declare the vehicle sold or stolen, or elect to go to Court.

In my experience, electing to go to Court will defer all further action for about 6 months, depending on how busy the courts are. Demerit points will not be applied to your License, and no money will be payable in that period. If you eventually lose your case, you will at least be well on the way to having fulfilled any penalty period, since the date of the alleged offence will be the starting point – not the Court date.

Step 1. Elect for a Court Hearing

Complete the Election for Court Hearing and get it posted ASAP, and preferably well within the 28 days that they stipulate. Keep a copy of your paperwork and use registered mail. Don’t bother paying to track it – Qld. Government mail goes through a security process that circumvents the Australia Post tracking system.

You’ll get a short form letter after a short while confirming receipt and saying a Court date will eventually be set via the issuance of a Summons. If you planned to go on a holiday, better get it done before the Summons is issued, because successive events beyond then occur at about 4 weekly intervals. In my case, there was a seven month delay before issuance of a Summons. The legislation requires that action must be commenced within 12 months of the alleged offence.

Step 2. Evaluate the Evidence

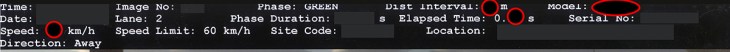

Learn what you can from the small photo provided in the original Infringement Notice. Use a magnifying glass if needed to establish the Model No. of the device used to capture the image, and the Distance Interval particular to the Location. Visit the location and try to determine which road markings represent the distance interval as displayed in the data block at the top of the image. In this way, you will have a good understanding of what to be looking for when you study the full size images. Consult Schedule 14 of the Traffic Regulations 1962 for the particular Device Model to assist you in understanding the data block information. The link to the Regulations is shown a few paragraphs below.

Telephone the Enquiries hotline shown at the top left of your Infringement Notice and ask that the images be made available for you to view at your local Police Station. You will be contacted in a few days by a local Police Officer to arrange a viewing on their computer at the Police Station. (You can pay for printed copies to be posted to you on payment of a fee, but I hate paying them any money whatever). You will eventually be provided with free images as part of their Brief of Evidence, so all you need at this point is a good idea of what is in them.

If a speed camera or combined camera is involved, there will likely be at least 2 photos. Your particular interest will lie in 2 areas –

a) the data block information at the top of each photo, particularly the items shown circled in the example below. The first image shows the elapsed time as zero, the second photo will show the elapsed time to the second image. Both photos show the alleged speed, proving that the speed has been determined prior to the images being captured (probably by radar):

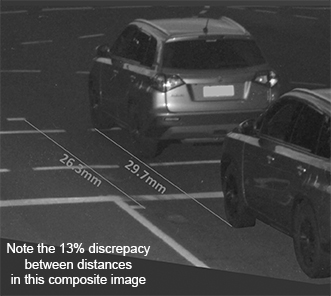

b) the position of the contact points of your front or rear tyres relevant to any painted road markings (these form the basis of the secondary speed verification system. In theory, if their speed as measured by radar is correct, the wheels will have traveled the same distance as the gap between the road markings during the time interval between each image. The composite image below depicts what to look for. If the speed reading is accurate, the two distances should be the same within a small margin of error – clearly not the case in this example. Simply use a ruler on the computer screen at the police station to compare the two distances. A Patent application by Redflex details how their particular secondary verification system is designed, and makes for very interesting reading for the technically inclined. Go to http://www.freepatentsonline.com/8712105.pdf and download the pdf file.

c) look for any other large metal objects in the photo that may have contributed to a false reading by reflection of the radar beam – eg a large stationary vehicle close to your own.

Also note the Model of the detection device so that you can look up its data block detail in the Schedule 14 as mentioned above..

The various speed detection devices used in Queensland are detailed in Schedule 14 of the Traffic Regulations 1962 that accompany TORUM. The Regulations can be viewed and downloaded here: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/2018-02-16/sl-1962-tr

The above link may fail as the legislation is updated periodically, but Google will be your friend in that case. Just search Traffic Regulations 1962 Schedule 14.

Step 3. Why is This Important?

If you can establish that their exists a discrepancy between the alleged speed and the information depicted in the photos, then it is theoretically possible to have the images disallowed as evidence. The Traffic Regulations 1962 states at s.210D 1(e) “if the tests or an image when viewed indicates a fault has affected the proper operation of the system as required under this section, the image must be rejected for evidentiary purposes” .

If the Magistrate declared the images inadmissable on the above grounds, I would expect that the prosecution would fail. The Redflex patent information states that a discrepancy of 10% or greater should be grounds for rejection.

If you want to subpoena your own independent witness regarding how the secondary verification system works, (assuming the device is of Redflex manufacture), then the 2 names given as the co-inventors of the Patent would be my suggestion. At time of writing, one of them still works for Redflex, and the second has moved to a computer software development company in Melbourne according to their respective LinkedIn profiles.

Step 4. If the Images are Consistent

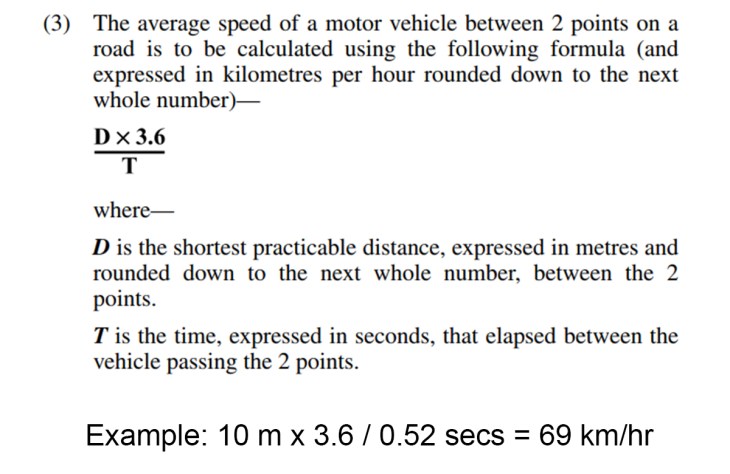

If the secondary verification system information detailed in the data block tends to support the alleged speed, then you will need to make a decision. The mathematics involved is defined in the legislation at TORUM 120A(3)

By my understanding of the operation of the secondary verification system, the time elapsed between image captures is only predictive and based on the above formula. The radar determines the alleged speed, and the image detection componentry predicts how long the vehicle will take to cover the fixed distance between the road markings using the above formula. Thus the time interval that elapses between the two image captures is dependent on the accuracy of the radar, and the person who evaluates the images is supposed to reject the result if the actual distance covered by your vehicle differs excessively from the particular design distance for the site as depicted by the specialised line markings on the road. The wording of the legislation in Schedule 14 is actually erroneous in my opinion, and should be challenged.

Once you get hold of the actual physical images as part of the Brief of Evidence, you can align them one above the other and use a sharp pin at the wheel contact point in the top photo. Then place the other photo on top and use the pin prick again. Then the distance between the pinpricks can be measured quite accurately and compared to the distance between the road markings that represent the Distance Interval for that Site. If the 2 measurements are very close, it would confirm that the radar reading was correct. In my case they exhibited a 13-14% discrepancy, due possibly to the fact that my vehicle was accelerating sharply through the measurement area, and radar speed measurement assumes that a vehicle is travelling at a constant speed.

If you were in fact exceeding the speed limit and no evidence of an equipment fault can be discerned, then it would probably be a good time to change your mind and pay the fine before the Court system gets into full swing through the issue of a Summons. This should prevent any additional costs and inconvenience being incurred by yourself.

Unless of course you have a valid reason for your actions.

Step 5. If Acting in Self Defence

Then you should have recourse to a s.25 (Qld. Criminal Code) defence as I did – Extraordinary Emergency. This is discussed by a person more qualified than me in the paper at this link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11147929_The_doctrine_of_necessity_and_medical_treatment

Download the pdf file using the call to action button at top right of the page. The relevant information states 3 basic requirements for a successful defence.

• the act must be done only to avoid certain consequences that would have inflicted evil

• the defendant must believe on reasonable grounds that it was a situation of peril. The time interval involved must be very brief

• the acts must be a proportional response to the peril and that a reasonable person would do the same

If you are unable to meet those criteria, then I would expect that it would be a difficult argument to win. In my case, I was able to secure video evidence from the traffic camera that tended to support my claim that I was about to be rear ended by a much larger vehicle, and was in fear of my life. Accelerating sharply into a clear space adjacent to me avoided a potentially fatal accident. The following vehicle was braking throughout the video to also avoid the collision, and could be proved to have been following much too closely.

My own experience suggests that it would be a good idea to have a rear facing dash cam installed in a car to help your case in any future mishap.

Step 6. Try to Find Some Video

Many, but not all, of the combined red light and speed cameras incorporate a video function that retains a 10 second clip centered around the alleged infringement. The good news is that you can get hold of this via a written right to information (RTI) request at no cost. Don’t make the mistake of asking for the still images – they will simply say they can be procured by paying the prescribed fee and direct you to the relevant procedure. Video clips by contrast are not mentioned in the legislation and so are provided at no cost to you if there are no valid reasons to refuse the application (public interest etc) Simply write to the RTI Unit. A sample format follows:

The Right to Information and Privacy Unit

Qld. Police Service,

GPO Box 1440

Brisbane Qld. 4001

Attention: Mr. A. Partington

Dear Sir,

Re: Video Footage of a Traffic Situation

I have been issued a Traffic Infringement Notice No. xxxxxxx relating to a minor alleged speed infringement.

I have elected to have this matter adjudicated by a Court.

The alleged infringement occurred at ….location.. at …time and date…… according to the photographic image provided to me.

In support of my defence, I require all available video evidence for the location and time in question covering 10 seconds either side of the indicated time. This application is made under the provisions of the Information Privacy Act 2009.

Please provide the video preferably in .mp4 format on media of your choice. A DVD or USB stick would be my preferred options.

As the prescribed evidence of my identity, a properly witnessed copy of my Driver’s License # xxxxxx is attached.

Correspondence relating to this request should be addressed to:

Name

Address 1

City and Postcode

Yours faithfully

Your Name

Attached: Certified copy of Drivers License # xxxxxx (Use a JP to certify the copy).

Step 7. Take Stock of the Evidence

If they provide a video, then analyse it closely. Read the Appendices A and B of AS 2898-2, which provide a good insight into the factors that can affect the accuracy of radar devices and the interpretation of images derived therefrom, even if the Standard is no longer acceptable as direct evidence in Court. You can be fairly confident that some of the these factors are given some attention in the Manufacturer’s Operating Guidelines.

A copy of Part 2 of the Standard appears at http://www.aussiespeedingfines.com/downloads/Radar_speed_detection_operational_procedures.pdf

Part 1 of the Standard is of no great practical value – simply a bunch of definitions etc.

I would be hesitant to use the copy at the above link in Court (copyright issues?). I preferred to buy a copy from Standards Australia, but in the end found a Section 25 defence (extraordinary emergency) was enough to secure the win. These Australian Standards are quite expensive, so don’t splash out on them unnecessarily.

In relation to the aussiespeedingfines web site, I have mixed feelings. I suspect that the methods and examples advocated by them are well known to the Police, and would attract little or no sympathy from a Magistrate. I actually subscribed to their book, but chose to be very selective as to use of their methods, and stayed well clear of the “3 step letter system” that they advocate. Some of the information provided by their subscribers was of more benefit by way of putting me on the right path for the Queensland system, particularly relating to the need to submit the Intention to Challenge Form. Interestingly, I provided aussiespeedingfines with a full dossier of my experience and win, but to date they have simply ignored it, perhaps because my account bears no relevance to their 3 step letter system.

Being computer literate, I found it beneficial to modify the video that I received from the police by applying a stop watch overlay onto the 10 second clip that they gave me. The police video was supplied at 25 frames per second, so the 2 decimal places stop watch could be seen to advance at 0.04 second intervals. To produce the overlay, I used freeware software called Lightworks in conjunction with a stop watch overlay video available at https://www.mediacollege.com/downloads/video/timecode/clock.html

I use VLC media player for viewing video, since it allows frame by frame advance (keyboard letter ‘E’) and is freeware.

This was potentially invaluable to me, because it provided additional proof that the radar speed and data block information in the still images differed from the video frames, casting more doubt on the accuracy of the radar reading.

If you want to get involved in the mathematics of speed and braking, then I would refer you to an excellent treatise on the subject published by AMSI. Just Google the term ‘AMSI braking distance’ or try this link:

Step 8. Get Ahead of the Game

Assuming that you are still intent on challenging the evidence in Court, or believe you have a valid Section 25 defence, the next hurdle that will come your way is the Summons. Once the Summons is issued, things seem to happen more quickly, and the stress levels rise.

So it’s best to prepare early, because a potential trap occurs right here.

Step 9. Beware the Trap

When the Summons is eventually issued, it will provide about 5 weeks notice of the first Court Date. Buried in the fine print that accompanies the Summons is a reminder that if you wish to challenge the accuracy of the speed camera, then you must provide at least 14 days clear notice of the grounds for your challenge ‘in the prescribed form’

I was alert to the requirement and found a relevant Form at this link: https:// https://www.support.transport.qld.gov.au/qt/formsdat.nsf/forms/QF4563/$file/F4563%20ES%20QP0784_Mar2015.pdf

I completed Section B of the form, ticked every box, and added about 300 pages of largely irrelevant material (cheeky, I know). I posted it to the Brisbane address given on the Form so that it arrived about 16 days prior to the Court Date. I suspect that many self represented defendants fail to provide this Intention to Challenge Form 14 days prior, and are ‘dead in the water’ before they even get started.

This immediately provoked an email response to my private email address (how did they know that?) which was the first serious engagement that the police had ever attempted. It was from the Senior Police Prosecutor no less, and he basically tried to find out the background story to my incident (potential rear end collision) and provided me with a second copy of the video as a ‘gesture of goodwill’. (I already had it via the earlier RTI request).

In his emails, the Senior Prosecutor went to great length to discredit my submission, saying that it was not in the correct form as required by a Court and would be greatly degraded as evidence in Court as a result. He also rebutted practically all of the cited decisions that I had included based on the aussiespeedingfines information that I had researched, and claimed that he could not see any reason in my argument to not proceed to Court. At this stage, I was unaware of the existence of Section 25 of the Criminal Code, but the prosecutor was left in no doubt that I had been trying to escape being rear ended. He clearly had no intention of helping me to achieve a just outcome by suggesting that a Section 25 defence would be appropriate. Only after I discovered it for myself and mentioned it to him in a subsequent face to face meeting following my initial ‘Not Guilty’ plea, did he suggest a course of action that he might consider favourably (see later).

Some of the emails from the Senior Prosecutor are marked as being illegal to copy, so of necessity the comments from the Senior Prosecutor are summarised in my own words as to my understanding of their content. My own responses have only identifying information altered, but are otherwise unaltered. The emails are listed in chronological order for ease of following the argument. My original submission is quite lengthy, but drew upon legal arguments espoused by aussiespeedingfines information, together with my own conclusions relating to the method of operation of the Redflex SR101 device that I had learned via the Patent documentation and other technical sheets found on the web. I think the email sequence gives a good insight to the QPS strategies when opposing people like myself:

Read on under ‘The Lead Up to Court’